Taproot recently activated on Bitcoin’s mainnet. The inclusion in Bitcoin’s protocol, however, is only the first step in actually reaping the benefits of Bitcoin’s latest upgrade.

“It’s been a long story that started in a diner in Los Altos, CA where Greg Maxwell, Andrew Poelstra and I somewhere in January 2018 had lunch.” – Pieter Wuille’s thread on the backstory of Taproot development and activation

The recent Bitcoin upgrade may be hard to grasp for non-technical bitcoiners — but that’s only when we focus on what it is and how it works on a technical level. That is the usual problem with communicating all things Bitcoin; sometimes we focus too much on the “what” and “how” of various Bitcoin elements, while overlooking the “why.”

The “why” of Taproot can be summed up as better Bitcoin. With Taproot, new possibilities for Bitcoin open up – advanced transactions such as Lightning Network channel management or multisigs are more efficient, private, and streamlined. In the future, only a minority of people will hold their own UTXOs on the base layer; the remaining billions will need a reliable second (and maybe even third or fourth) layer on top of the base layer. Taproot is an important step towards this future, as it makes the layered evolution of Bitcoin more accessible than ever before. And those that develop the Bitcoin tools have a responsibility to implement the catalysts for long-term improvement such as Taproot without an unnecessary delay.

Taproot in general has been extensively covered on these pages by other authors. In this text, we won’t repeat what has already been said, but rather cover Taproot from the specific perspective of hardware wallet users.

New Address Type

The first element relevant to wallet users is that Taproot brings new address types. The original SegWit (SegWit v0, encoded in bech32) addresses started with “bc1q”, whereas Taproot addresses (SegWit v1, encoded in bech32m) will read “bc1p”. This may seem like a technicality, but the fact is that Taproot addresses will not be automatically supported by wallets and services that currently support only the original SegWit. Wallet developers, exchanges and other service providers need to actively implement the new address type, just as they had to do so for SegWit v0. The current state of support among major exchanges and wallets can be found at Bitcoin Wiki (columns indicating support of Bech32m and P2TR are relevant to Taproot).

An interesting factoid of Taproot addresses is that their length is 62 characters, whereas SegWit addresses are only 42 characters (legacy addresses starting with “1” or “3” were 34 characters).

Trezor will roll out the support for Taproot addresses in December of this year. This means that after the user installs a new firmware, the new address type will show up in the account type selection. Of course, users are free not to use the Taproot address type as all the previous address types will be supported indefinitely.

Compatibility

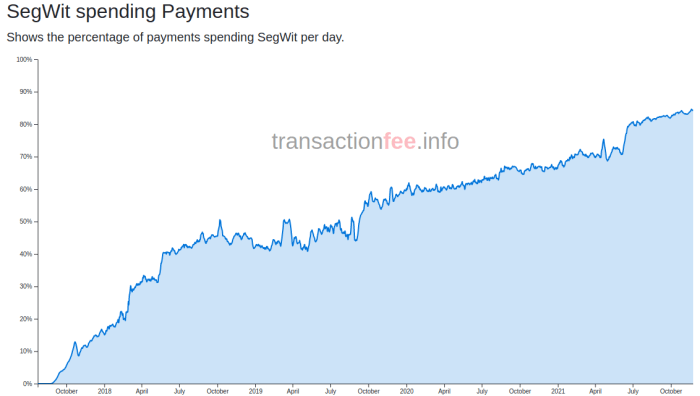

With a new address type comes the headache of compatibility. When the original SegWit was implemented by the first wallets in 2017, the new address type was invalid for most of the other wallets, and exchanges which were slow to adopt it. Rollout of the new address type is a bit of a chicken and egg problem: users can’t use it, because developers haven’t implemented it, because users don’t widely use it. This conundrum is only solvable with developers being proactive in rolling out the new feature that will ultimately benefit the whole Bitcoin ecosystem.

It took two years for SegWit to be used in at least half of all Bitcoin transactions, even though there was no downside in using it and users were rewarded with fee savings (and in the long run, the possibility to transact over the Lightning Network, for which SegWit was the necessary prerequisite). It’s quite possible that it will take several years for Taproot to be widely used as well.

Hopefully the transition to Taproot addresses will be more straightforward than transition to SegWit addresses, because most of the hard work has already been done. To enable sending to Taproot, one has only to implement the new Bech32m encoding and enable the v1 version field in SegWit scripts.

So even though users will be able to generate their Taproot addresses in Trezor and migrate their sats over to this new format, it’s possible that many other wallets and exchanges won’t recognize it, so users may have to stick to the original SegWit address type for the time being when interacting with the broader Bitcoin ecosystem.

Cheaper fees

Similar to SegWit, Taproot transactions reduce the transaction weight, which translates to cheaper fees. However, this is only the case when spending from the Taproot address. Sending to a Taproot address can be more expensive than sending to a SegWit address. Below are the relevant sizes of transaction elements (colors indicate the cheaper one):

- SegWit: send to public key hash = 20 bytes; sign with ECDSA signature = up to 72 bytes

- Taproot: send to public key = 32 bytes; sign with Schnorr signature = 64 bytes

Weight/fee savings related to Taproot are heavily conditional on the type of transactions the user is looking to perform from the Taproot addresses. For basic transactions (e.g. 1 input, 2 outputs, with no complex spending conditions involved) there are no savings – in fact, users might even pay slightly more with Taproot; but for advanced transactions with many inputs and complex spending conditions, the transaction weight could be cut in half or even more over the non-Taproot alternative, and the resulting fee savings are considerable.

In other words, spending Taproot UTXOs does bring cheaper fees, but the savings will be mostly enjoyed when dealing with complex spending conditions structures (called MAST), opening up the possibility of advanced transaction types that would have been prohibitively expensive up until now.

For hardware wallet users, this will mostly translate to cheaper multisignature operations:

Increased Privacy

Taproot’s potential privacy benefits are only tangential. The main privacy advantage of Taproot is a potential obfuscation of transaction types, where advanced transactions such as Lightning Network channel openings/closings or multisig transactions might become indistinguishable from simple spends. Why are the benefits only potential? Because to reap them, Taproot transactions need to be widespread – which, as we’ve already covered, will probably take years.

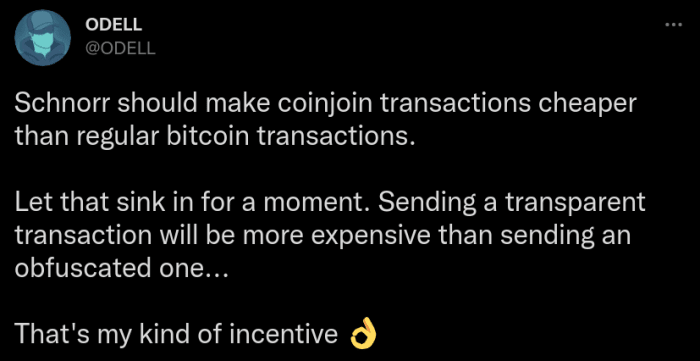

In future versions of Taproot (yes, we’ll likely see further upgrades of this upgrade), the privacy gains can be more substantial. Schnorr signatures allow for something called cross-input signature aggregation (CISA), where signatures made from multiple unrelated wallets could be aggregated into a single signature; this would be mainly relevant to CoinJoin transactions (Trezor is implementing CoinJoin in the Suite interface in 2022). If this became possible, CoinJoins from your hardware wallet could become an ubiquitous way to spend your bitcoin: as Matt Odell pointed out in the past, a CoinJoin transaction can eventually become even cheaper than a simple spend. However, to reiterate: this is not yet possible with the current Taproot implementation.

Other Major Benefits

Taproot patches the longstanding theoretical fee exploit, where the wallet user might be tricked into sending a transaction that would drain their account through an exorbitant transaction fee. This exploit could target multi-input transactions, where the attacker could leverage the fact that under SegWit v0, each input committed only to the input amount of itself (details of the potential exploit are described here). While the potential exploit has been patched in the major hardware wallets, this caused a lot of headache for some projects and some wallets might still be vulnerable. SegWit v1 solves this problem for good, as each input is commiting not only to their own amount, but also to amounts of other inputs. So it is now impossible to craft special fake inputs that are needed to perform this attack.

And finally, a major benefit for hardware wallet users is a streamlined transaction signing and broadcasting process, especially when a large number of transaction inputs are involved. With Taproot, the wallet no longer needs to send the often extensive history of transactions which preceded the one being spent. While users performing simple spends won’t necessarily notice this benefit, it helps especially with CoinJoin transactions. The pre-Taproot necessity of streaming the transaction history made CoinJoins an impractical prospect for hardware wallets; this changes now, and it will soon be possible to enjoy the enhanced transactional privacy that CoinJoins bring straight from the safety of your hardware wallet.

This is a guest post by Josef Tětek. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

Credit: Source link

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  Solana

Solana  XRP

XRP  Dogecoin

Dogecoin  Cardano

Cardano  USDC

USDC  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  TRON

TRON  Avalanche

Avalanche  Stellar

Stellar  Toncoin

Toncoin  Shiba Inu

Shiba Inu  Wrapped stETH

Wrapped stETH  Wrapped Bitcoin

Wrapped Bitcoin  Polkadot

Polkadot  Chainlink

Chainlink  Bitcoin Cash

Bitcoin Cash  Sui

Sui  WETH

WETH  Pepe

Pepe  LEO Token

LEO Token  NEAR Protocol

NEAR Protocol  Litecoin

Litecoin  Aptos

Aptos  Uniswap

Uniswap  Wrapped eETH

Wrapped eETH  Hedera

Hedera  Internet Computer

Internet Computer  Cronos

Cronos  USDS

USDS  POL (ex-MATIC)

POL (ex-MATIC)  Ethereum Classic

Ethereum Classic  Render

Render  Bittensor

Bittensor  Artificial Superintelligence Alliance

Artificial Superintelligence Alliance  Ethena USDe

Ethena USDe  Bonk

Bonk  Arbitrum

Arbitrum  Cosmos Hub

Cosmos Hub  WhiteBIT Coin

WhiteBIT Coin  Filecoin

Filecoin  Dai

Dai  dogwifhat

dogwifhat  MANTRA

MANTRA  Stacks

Stacks